Recordando a Gram Parsons

It was late summer 1973, just weeks before Parsons would be found dead of an overdose in a Joshua Tree motel room at the age of 26. The California singer had been slowly fading into an abyss of drugs and alcohol for several years by the time he entered the studios in Los Angeles to begin work on what would be his second, and final, studio album. So much so that Parsons, who’d been a fairly prolific songwriter throughout his short-lived career, only managed to write one entirely new song for the upcoming Grievous Angel sessions. That song was called “In My Hour of Darkness.”

“And I knew his time would shortly come,” Parsons sings on the mournful ballad. “But I did not know just when.”

When his sister Avis reflected on the album years later, she didn’t hear the masterwork Parsons had told her he’d made; she heard a farewell. “He wanted to go out in a great flash of glory rather than fade away,” she told Fong-Torres. “Look how beautifully he got himself together for that last album. Son of a bitch. I’m really pissed at him.”

In the nearly 50 years since the posthumous 1974 release of Grievous Angel, the legend and legacy of Gram Parsons has metastasized into something more than myth. The journeyman singer-songwriter had spent around seven years rotating among a series of bands in his pursuit of incorporating the country music of his native South Georgia into the rock, pop and folk blooming in late-’60s Los Angeles, with virtually zero commercial success. But since his death, Parsons has become an avatar and a guidepost for several successive generations of artists attempting, often with more success than Parsons, to present elements of traditional American country and roots music in non-strictly country settings.

Most enduringly, Parsons co-wrote several songs (“Sin City” and “Hickory Wind” among them) during his lifetime that have become bona fide standards since his death. “Hickory Wind” alone — an aching duet with his primary creative partner, Emmylou Harris — has been covered by Lucinda Williams, Gillian Welch, Joan Baez, Jay Farrar, Norah Jones, Billy Strings, Ashley Monroe, Keith Whitley, Mo Pitney, the Tuttles, the Seldom Scene and Parsons’ old friend Keith Richards.

Long after, artists ranging from Wilco, Sheryl Crow, the Lemonheads and Whiskeytown all professed their allegiance to Parsons during the alt-country ’90s. And the singer-songwriter’s music still looms large. Ruston Kelly and Ashley Monroe released a cover of Harris and Parsons’ rendition of “Love Hurts” during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Swedish roots-pop duo First Aid Kit broke out in America in the early 2010s with “Emmylou,” a romantic ode to the music of Harris and Parsons, complete with a seance-like music video filmed in Parsons’ beloved Joshua Tree. The sisters had discovered Harris by listening to her duet singing on Grievous Angel.

“It was a revelation for us,” they said of hearing the music of Parsons and Harris for the first time.

Parsons’ music has provided that sense of revelation for nearly 50 years, presenting what now feels like an effortless vision of what it meant to merge the rowdy honky-tonk of George Jones and the riotous rock ’n’ roll of Elvis Presley with the folk-pop balladry of The Everly Brothers. Still, as is so often the case with posthumous releases, it’s nearly impossible to separate Grievous Angel’s myth from its music. Shrouded in aura through the 20/20 lens of Parsons’ tragic death, the album has never stopped growing in stature.

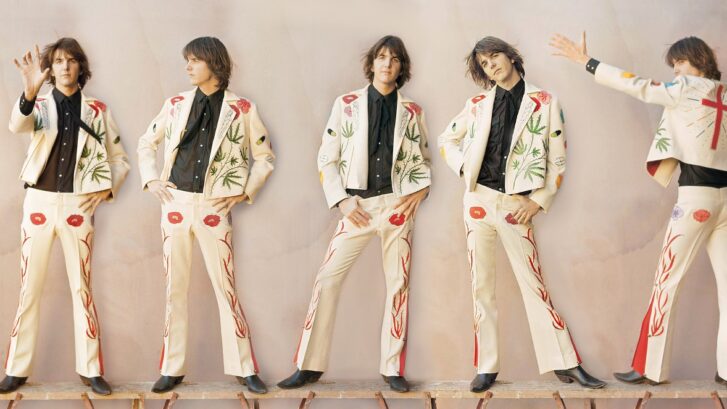

Even during his life, Parsons was always keenly aware of his own mythology. Parsons, whose mother was part of a troubled Florida family that oversaw a fortune in citrus production, was an occasionally nihilistic trust-fund delinquent whose backstory and aura of casual recklessness gave the rock press far more interesting copy than most country singers of the time.